List the principles of art

1.6: What Are the Elements of Art and the Principles of Art?

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 46130

- Deborah Gustlin & Zoe Gustlin

- Evergreen Valley College via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative

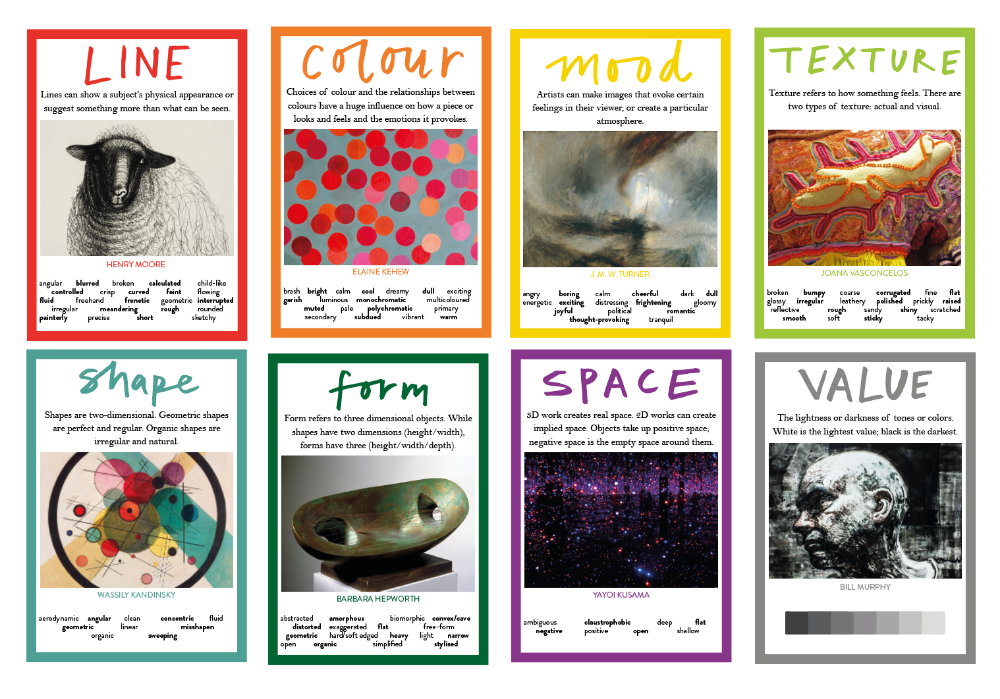

The visual art terms separate into the elements and principles of art. The elements of art are color, form, line, shape, space, and texture. The principles of art are scale, proportion, unity, variety, rhythm, mass, shape, space, balance, volume, perspective, and depth. In addition to the elements and principles of design, art materials include paint, clay, bronze, pastels, chalk, charcoal, ink, lightening, as some examples. This comprehensive list is for reference and explained in all the chapters. Understanding the art methods will help define and determine how the culture created the art and for what use.

Over the years, art methods have changed; for example, the acrylic paint used today is different from the cave art earth-based paint used 30,000 years ago. People have evolved, discovering new products and procedures for extracting minerals from the earth to produce art products. From the stone age, the bronze, iron age, to the technology age, humans have always sought out new and better inventions. However, access to materials is the most significant advantage for change in civilizations. Almost every civilization had access to clay and was able to manufacture vessels. However, if specific raw materials were only available in one area, the people might trade with others who wanted that resource. For example, on the ancient trade routes, China produced and processed the raw silk into stunning cloth, highly sought out by the Venetians in Italy to make clothing.

1.24 Mondrian compositionThe art methods are considered the building blocks for any category of art. When an artist trains in the elements of art, they learn to overlap the elements to create visual components in their art. Methods can be used in isolation or combined into one piece of art (1.24), a combination of line and color. Every piece of art has to contain at least one element of art, and most art pieces have at least two or more.

When an artist trains in the elements of art, they learn to overlap the elements to create visual components in their art. Methods can be used in isolation or combined into one piece of art (1.24), a combination of line and color. Every piece of art has to contain at least one element of art, and most art pieces have at least two or more.

Elements of Art

Color: Color is the visual perception seen by the human eye. The modern color wheel is designed to explain how color is arraigned and how colors interact with each other. In the center of the color wheel, are the three primary colors: red, yellow, and blue. The second circle is the secondary colors, which are the two primary colors mixed. Red and blue mixed together form purple, red, and yellow, form orange, and blue and yellow, create green. The outer circle is the tertiary colors, the mixture of a primary color with an adjacent secondary color.

1.25 Color WheelColor contains characteristics, including hue, value, and saturation. Primary hues are also the primary colors: red, yellow, and blue. When two primary hues are mixed, they produce secondary hues, which are also the secondary colors: orange, violet, and green. When two colors are combined, they create secondary hues, creating additional secondary hues such as yellow-orange, red-violet, blue-green, blue-violet, yellow-green, and red-orange.

Primary hues are also the primary colors: red, yellow, and blue. When two primary hues are mixed, they produce secondary hues, which are also the secondary colors: orange, violet, and green. When two colors are combined, they create secondary hues, creating additional secondary hues such as yellow-orange, red-violet, blue-green, blue-violet, yellow-green, and red-orange.

Value: refers to how adding black or white to color changes the shade of the original color, for example, in (1.26). The addition of black or white to one color creates a darker or lighter color giving artists gradations of one color for shading or highlighting in a painting.

1.26 Hue, saturation, and valueSaturation: the intensity of color, and when the color is fully saturated, the color is the purest form or most authentic version. The primary colors are the three fully saturated colors as they are in the purest form. As the saturation decreases, the color begins to look washed out when white or black is added. When a color is bright, it is considered at its highest intensity.

When a color is bright, it is considered at its highest intensity.

Form: Form gives shape to a piece of art, whether it is the constraints of a line in a painting or the edge of the sculpture. The shape can be two-dimensional, three-dimensional restricted to height and weight, or it can be free-flowing. The form also is the expression of all the formal elements of art in a piece of work.

1.28 FormLine: A line in art is primarily a dot or series of dots. The dots form a line, which can vary in thickness, color, and shape. A line is a two-dimensional shape unless the artist gives it volume or mass. If an artist uses multiple lines, it develops into a drawing more recognizable than a line creating a form resembling the outside of its shape. Lines can also be implied as in an action of the hand pointing up, the viewer's eyes continue upwards without even a real line.

1.29 LineShape: The shape of the artwork can have many meanings. The shape is defined as having some sort of outline or boundary, whether the shape is two or three dimensional. The shape can be geometric (known shape) or organic (free form shape). Space and shape go together in most artworks.

The shape can be geometric (known shape) or organic (free form shape). Space and shape go together in most artworks.

Space: Space is the area around the focal point of the art piece and might be positive or negative, shallow or deep, open, or closed. Space is the area around the art form; in the case of a building, it is the area behind, over, inside, or next to the structure. The space around a structure or other artwork gives the object its shape. The children are spread across the picture, creating space between each of them, the figures become unique.

1.31 SpaceTexture: Texture can be rough or smooth to the touch, imitating a particular feel or sensation. The texture is also how your eye perceives a surface, whether it is flat with little texture or displays variations on the surface, imitating rock, wood, stone, fabric. Artists added texture to buildings, landscapes, and portraits with excellent brushwork and layers of paint, giving the illusion of reality.

Principles of Art

Balance: The balance in a piece of art refers to the distribution of weight or the apparent weight of the piece. Arches are built for structural design and to hold the roof in place, allowing for passage of people below the arch and creating balance visually and structurally. It may be the illusion of art that can create balance.

1.33 BalanceContrast: Contrast is defined as the difference in colors to create a piece of visual art. For instance, black and white is a known stark contrast and brings vitality to a piece of art, or it can ruin the art with too much contrast. Contrast can also be subtle when using monochromatic colors, giving variety and unity the final piece of art.

1.34 ContrastEmphasis: Emphasis can be color, unity, balance, or any other principle or element of art used to create a focal point. Artists will use emphasis like placing a string of gold in a field of dark purple. The color contrast between the gold and dark purple causes the gold lettering to pop out, becoming the focal point.

Rhythm/Movement: Rhythm in a piece of art denotes a type of repetition used to either demonstrate movement or expanse. For instance, in a painting of waves crashing, a viewer will automatically see the movement as the wave finishes. The use of bold and directional brushwork will also provide movement in a painting.

1.36 Rhythm/MovementProportion/Scale: Proportion is the relationship between items in a painting, for example, between the sky and mountains. If the sky is more than two-thirds of the painting, it looks out of proportion. The scale in art is similar to proportion, and if something is not to scale, it can look odd. If there is a person in the picture and their hands are too large for their body, then it will look out of scale. Artists can also use scale and proportion to exaggerate people or landscapes to their advantage.

1.37 Proportion and ScaleUnity and variety: In art, unity conveys a sense of completeness, pleasure when viewing the art, and cohesiveness to the art, and how the patterns work together brings unity to the picture or object. As the opposite of unity, variety should provoke changes and awareness in the art piece. Colors can provide unity when they are in the same color groups, and a splash of red can provide variety.

As the opposite of unity, variety should provoke changes and awareness in the art piece. Colors can provide unity when they are in the same color groups, and a splash of red can provide variety.

Pattern: Pattern is the way something is organized and repeated in its shape or form and can flow without much structure in some random repetition. Patterns might branch out similar to flowers on a plant or form spirals and circles as a group of soap bubbles or seem irregular in the cracked, dry mud. All works of art have some sort of pattern even though it may be hard to discern; the pattern will form by the colors, the illustrations, the shape, or numerous other art methods.

1.39 Pattern- Back to top

- Was this article helpful?

-

- Article type

- Section or Page

- Author

- Deborah Gustlin & Zoe Gustlin

- License

- CC BY

- License Version

- 4.

0

0

- OER program or Publisher

- ASCCC OERI Program

- Show TOC

- yes

- Tags

-

What They Are and How to Use Them Effectively

The principles of art (or the principles of design) are essentially a set of criteria that are used to explain how the visual elements are arranged in a work of art. These principles are possibly the closest thing we have to a set of objective criteria for analyzing and judging art.

Art is a notoriously gray area when it comes objectively defining what is great and what is not. An artist of one era may be mocked during his lifetime, yet revered after his passing (such as Vincent van Gogh). The principles of art help combat this gray area to some extent. They allow us to communicate what makes a great painting great with an element of objectivity and consistency.

They allow us to communicate what makes a great painting great with an element of objectivity and consistency.

The following is an explanation of what the principles of art are and how you can use them to benefit your own artworks. I cover:

- Pattern

- Balance

- Emphasis

- Contrast

- Harmony And Unity

- Variety

- Movement

- Proportion

- Scale

- Summary

- Want to Learn More?

- Thanks for Reading!

Pattern

Pattern is a very important design concept that refers to the visual arrangement of elements with a repetitive form or intelligible sequence.

Pattern is not always obvious. It could be a simple underlying notan design that dances between light and dark in some kind of sequence. Or it could be the use of similar color patterns throughout your painting.

In the painting below, notice how the top arm of the subject almost blends into the background, and how the legs blend into the cloth, and the cloth blends into the rest of the foreground. This interlinking pattern drags you through the painting and creates a very interesting design.

This interlinking pattern drags you through the painting and creates a very interesting design.

Balance

Balance is concerned with the visual distribution or weight of the elements in a work of art. A painting could be balanced if one half is of the same visual weight as the other half. Or, you could have a small area of heightened significance which is balanced against a much larger area of less significance, like in the painting below. In the painting below, notice how the dark areas used for the boat and foreground appear balanced against the much larger area of soft, tinted colors.

Efim Volkov, Seascape, 1895Emphasis

Emphasis is a way of using elements to stress a certain area in an artwork. Emphasis is really just another way to describe a focal point in your artwork. In the painting below, there is a strong emphasis on the moon through the use of color contrast.

George Henry, River Landscape By Moonlight, 1887(See the supplies page for details about what I use and recommend. )

)

Contrast

Contrast is everything in art. Without it, artwork would be nothing but a blank surface. Contrast can come in many forms:

Texture contrast: A contrast between smooth and textured. Many of Vincent van Gogh’s paintings are great examples of texture contrast in action.

Color contrast: A contrast between light and dark, saturated and dull or complementary colors (hue contrast). For example, in the painting below, the highly saturated red contrasts against the relatively dull colors in the rest of the painting.

Joaquin Sorolla, Father Jofre Protecting A Madman, 1887Detail contrast: A contrast between areas of detail and more bland areas, like in the painting below.

Rudolf von Alt, View Of Ragusa, 1841Shape contrast: A contrast between different shapes (rectangles and circles). For example, in the painting there are the curving shapes created by the winding paths, water and trees contrast against the rectangular shapes of the buildings.

Interval contrast: A contrast between long and short intervals. In the painting below, notice the variation in the lengths of the intervals between the trees. The interval contrast can be used to create a sense of rhythm in your artwork.

Isaac Levitan, Oak Grove, Autumn, 1880Harmony And Unity

Harmony is a bit vague compared to some of the other principles. Generally speaking, it refers to how well all the visual elements work together in a work of art. Elements that are in harmony should have some kind of logical progression or relationship. If there is an element that is not in harmony with the rest of an artwork, it should stick out and be jarring to look at. Kind of like an off-note in a song.

You will usually be able to tell just from judgment if all the elements are in harmony. It will just look right. However, if the painting looks off, then it can be difficult to tell if that is because there is no harmony between the elements or if there is some other issue.

When I think of harmony, I think of the peaceful arrangements of color in Monet’s series of water lilies.

Claude Monet, Water Lilies, 1908Unity refers to some kind of connection between all the visual elements in a work of art. Like harmony, this is a bit of a vague term which is difficult to objectively use to analyze art. The painting below demonstrates a strong sense of unity through the use of a similar hues used throughout the painting. Even though there is a strong contrast between the light and dark areas, there is a sense of unity created through the use of similar hues (dark yellows, oranges and greens are used in the foreground and light yellows, oranges and greens are used in the background).

George Henry, Noon, 1885Variety

Variety refers to the use of differing qualities or instances of visual elements. Variety can be used to break up monotonous or repetitive areas.

Below is a painting with lots of variation in color, shape and texture, yet not so much that it loses any sense of harmony.

Below is a painting with comparatively less variance. The result is a much calmer painting.

Lake Keitele, Akseli Gallen-Kallela, 1905Movement

Your paints cannot physically move, but you can arrange the paints in a way which gives the illusion or suggestion of movement.

One of the most effective techniques for creating movement in your painting is to use bold and directional brushwork. By doing this, you can suggestively push your viewer around the painting as you please. You could also suggest movement through repetition or pattern.

Below are two examples of paintings that demonstrate a great sense of movement.

Joaquín Sorolla, Sea And Rocks – Javea, 1900 Frederick Judd Waugh, Breaking SurfAlso, I could not talk about using movement in art without some mention of Vincent van Gogh.

Vincent van Gogh, Starry Night Over The Rhone, 1888Proportion

Proportion concerns the relationship between the sizes of different parts in an artwork. For example, the width compared to the length, the area of the sky compared to the land or the area of foreground compared to the background.

For example, the width compared to the length, the area of the sky compared to the land or the area of foreground compared to the background.

Some proportions are considered to be visually pleasing, such as the rule of thirds and the golden ratio.

In the painting below by Giovanni Boldini, notice how the proportions of the female subject’s hands, face, feet and torso are all accurate. If Boldini painted the hand too large compared to the rest of the subject’s body, there would be an issue of proportion.

Giovanni Boldini, A Guitar Player, 1873Scale

Scale refers to the size of an object compared to the rest of the surroundings. For example, the size of a man compared to the tree he is sitting under or the size of a mountain compared to the clouds. Scale is different to proportion in that scale refers to the size of an entire object whereas proportion refers to the relative size of parts of an object. For example, the scale of a man relative to the rest of the painting may be correct, but the proportion might be wrong because his hands are too large.

Summary

I hope this post clarifies to you what the principles of art are and how you can use them to help understand and communicate your thoughts about art.

It is also important to understand that a great painting does not have to tick all the boxes in terms of the principles of art. Most of the great paintings will only demonstrate a few of the principles.

So do not think of the principles of art as a set of overarching rules which you must comply with. They are merely a way to help us understand and communicate our thoughts about art.

The principles of art allow us to place some kind of objective reasoning behind why a great painting is great. This is important as it keeps us from falling into a vague space where art is no longer able to be defined or critiqued (much like what has happened with modern art).

Want to Learn More?

You might be interested in my Painting Academy course. I’ll walk you through the time-tested fundamentals of painting. It’s perfect for absolute beginner to intermediate painters.

It’s perfect for absolute beginner to intermediate painters.

Thanks for Reading!

I appreciate you taking the time to read this post and I hope you found it helpful. Feel free to share it with friends.

Happy painting!

Dan Scott

Draw Paint Academy

About | Supply List | Featured Posts | Products

§ 2. Basic principles of art

In the process of historical functioning in Culture, a whole system of principles was developed on which art was based in one or another cultural and historical area. Here we are talking

263

only about the art of the European-Mediterranean area in the historical interval from Ancient Egypt to Euro-American art of the 20th century, which by the beginning of the 20th century. penetrated almost all continents, but it nevertheless does not cover human art as a whole. Today, it is obvious to us, Europeans, that this Euro-American paradigm is not sufficient to describe, for example, the traditional (classical) arts of the East, pre-Columbian America, the peoples of Black Africa or Oceania. In this book, with all the breadth of the general significance of aesthetic principles, we still limit them to the field of classical European culture that has developed over the past few millennia and is still relevant for Russia. nine0003

In this book, with all the breadth of the general significance of aesthetic principles, we still limit them to the field of classical European culture that has developed over the past few millennia and is still relevant for Russia. nine0003

In this chapter we will dwell in more detail on the system of basic artistic principles of art, quite clearly identified by classical aesthetics. Having comprehended art as a unique phenomenon of a concrete-sensual expression of a certain semantic reality that is not amenable to any other forms and methods of expression, we set ourselves the task of identifying the specifics of this expression, its basic principles.

Mimesis

Since antiquity, European philosophical thought has shown quite clearly that the basis of art as a special human activity is mimesis - a specific and diverse imitation (although this Russian word is not an adequate translation of the Greek, therefore, in the future we more often, which is accepted in aesthetics, we will use the Greek term without translation). Based on the fact that all arts are based on mimesis, thinkers of antiquity interpreted the very essence of this concept in different ways. The Pythagoreans believed that music imitated "the harmony of the heavenly spheres"; Democritus was convinced that art in its broadest sense (as a productive creative activity of a person) comes from the imitation of a person by animals (weaving from imitation of a spider, house-building - to a swallow, singing - to birds, etc.). A more detailed theory of mimesis was developed by Plato and Aristotle. At the same time, they endowed the term "mimesis" with a wide range of meanings, Plato believed that imitation is the basis of all creativity. Poetry, for example, can imitate truth and goodness. However, usually the arts are limited to imitation of objects or phenomena of the material world, and in this Plato saw their limitations and imperfections, because they themselves

Based on the fact that all arts are based on mimesis, thinkers of antiquity interpreted the very essence of this concept in different ways. The Pythagoreans believed that music imitated "the harmony of the heavenly spheres"; Democritus was convinced that art in its broadest sense (as a productive creative activity of a person) comes from the imitation of a person by animals (weaving from imitation of a spider, house-building - to a swallow, singing - to birds, etc.). A more detailed theory of mimesis was developed by Plato and Aristotle. At the same time, they endowed the term "mimesis" with a wide range of meanings, Plato believed that imitation is the basis of all creativity. Poetry, for example, can imitate truth and goodness. However, usually the arts are limited to imitation of objects or phenomena of the material world, and in this Plato saw their limitations and imperfections, because they themselves

264

he understood objects of the visible world only as weak "shadows" (or imitations) of the world of ideas. The actual aesthetic concept of mimesis belongs to Aristotle. It includes both an adequate reflection of reality (the depiction of things as “the way they were or are”), and the activity of creative imagination (their depiction as “they are spoken and thought about”), and the idealization of reality (their depiction as such, “ what they should be). Depending on the creative task, the artist can consciously either idealize, elevate his characters (as a tragic poet does), or present them in a funny and unattractive way (which is inherent in the authors of comedies), or portray them in their usual form. The purpose of mimesis in art, according to Aristotle, is the acquisition of knowledge and the excitation of a feeling of pleasure from the reproduction, contemplation and cognition of an object. nine0003

The actual aesthetic concept of mimesis belongs to Aristotle. It includes both an adequate reflection of reality (the depiction of things as “the way they were or are”), and the activity of creative imagination (their depiction as “they are spoken and thought about”), and the idealization of reality (their depiction as such, “ what they should be). Depending on the creative task, the artist can consciously either idealize, elevate his characters (as a tragic poet does), or present them in a funny and unattractive way (which is inherent in the authors of comedies), or portray them in their usual form. The purpose of mimesis in art, according to Aristotle, is the acquisition of knowledge and the excitation of a feeling of pleasure from the reproduction, contemplation and cognition of an object. nine0003

Neoplatonist Plotinus, deepening the ideas of Plato, saw the meaning of arts in imitation not of appearance, but of the very visual ideas (eidoses) of visible objects, i.e. in the expression of their essential (=beautiful in his aesthetics) primordial foundations. These ideas, already on a Christian basis, were rethought in the 20th century. neo-Orthodox aesthetics, especially consistently by S. Bulgakov, as we have seen (ch. I. § 1.), into the principle of sophianism of art.

These ideas, already on a Christian basis, were rethought in the 20th century. neo-Orthodox aesthetics, especially consistently by S. Bulgakov, as we have seen (ch. I. § 1.), into the principle of sophianism of art.

Artists of antiquity most often focused on one of these aspects of the understanding of mimesis. Thus, in the ancient Greek theory and practice of the fine arts, there was a tendency to create illusory images (for example, the famous bronze “Heifer” of Myron, seeing which the bulls mooed with lust; or the artist’s image of grapes

Zeuxis, which, according to legend, birds flocked to peck), which help to understand, for example, late examples of such painting, preserved on the walls of the houses of the Roman city of Pompeii, once covered with the ashes of Vesuvius. In general, the Hellenic fine arts are characterized by an implicit understanding of mimesis as an idealizing principle of art, i.e. extraconscious adherence to the concept of depicting the visual eidos of things and phenomena, which was verbally recorded by Plotinus only in the period of late Hellenism. Subsequently, this trend was followed by artists and theorists of the art of the Renaissance and classicism. In the Middle Ages, the mimetic concept of art was characteristic of Western European painting and sculpture, while in Byzantium its specific variety, the symbolic image, dominated; the term "mimesis" itself is filled with new content in Byzantium. In Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, for example, as we have seen

Subsequently, this trend was followed by artists and theorists of the art of the Renaissance and classicism. In the Middle Ages, the mimetic concept of art was characteristic of Western European painting and sculpture, while in Byzantium its specific variety, the symbolic image, dominated; the term "mimesis" itself is filled with new content in Byzantium. In Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, for example, as we have seen

265

in chap. I, “inimitable imitation” is a symbolic image, “in contrast” denoting an incomprehensible archetype.

In post-Renaissance (New European) aesthetics, the concept of mimesis merged into the context of "imitation theory", which at different stages of the history of aesthetics and in various schools, directions, currents understood "imitation" (or mimesis) often in very different senses (often in diametrically opposed ), nevertheless ascending to a wide ancient-medieval semantic spectrum: from illusory-photographic imitation of the visible forms of material objects and life situations (naturalism, photorealism) through a conditionally generalized expression of typical images, characters, actions of everyday reality (realism in its various forms) to "imitation" of some original ideal principles, ideas, archetypes, inaccessible to direct vision (romanticism, symbolism, some areas of avant-garde art of the twentieth century). nine0003

nine0003

In general in the visual arts from ancient times to the beginning of the twentieth century. the mimetic principle was dominant, because the magic of imitation - the creation of a copy, likeness, visual double, the display of transient material objects and phenomena, the desire to overcome time by perpetuating their appearance in more durable materials of art is genetically inherent in man. Only with the advent of photography did it begin to wane, and most avant-garde and modern art (see: Section Two) consciously abandon the mimetic principle in the elitist visual arts. It persists only in popular art and conservative commercial production. nine0003

In the most "advanced" art practices of the twentieth century. mimesis is often replaced by a real presentation of the thing itself (and not its likeness) and the activation of its real energy in the context of a specially created art space, or simulacra are created - pseudo-similarity that have no prototypes at any level of being or existence. And here the nostalgia for illusory imitations is growing. As a result, photography (especially old photography), documentary film and video images, and documentary sound recordings are beginning to take an increasing place in the most modern art projects. Today it is quite obvious that mimesis is an inalienable need of human activity and, in principle, cannot be excluded from the aesthetic experience of a person, no matter what historical transformations he may undergo. And thus, it remains the essential principle of art, although in the twentieth century. its range has greatly expanded from the presentation of the thing itself as a work of art (mimesis only by changing

And here the nostalgia for illusory imitations is growing. As a result, photography (especially old photography), documentary film and video images, and documentary sound recordings are beginning to take an increasing place in the most modern art projects. Today it is quite obvious that mimesis is an inalienable need of human activity and, in principle, cannot be excluded from the aesthetic experience of a person, no matter what historical transformations he may undergo. And thus, it remains the essential principle of art, although in the twentieth century. its range has greatly expanded from the presentation of the thing itself as a work of art (mimesis only by changing

266

the context of the functioning of a thing from everyday to artistic exposition) to a simulacrum - a conscious artistic "deception" of the recipient (ironic game) in postmodernism by presenting as an "imitation" of a certain image, in principle, having no prototype, i.e. . object of imitation. In both cases, the principle of mimesis is practically taken beyond its semantic boundaries, testifying to the end of classical aesthetics and classical (= mimetic) art. nine0003

nine0003

The essence of mimetic art as a whole is isomorphic (preserving a certain similarity of forms) display, or expression with the help of images. Art is figurative, i.e. fundamentally non-verbalizable (not adequately transmitted in speech verbal constructions, or formal logical discourse) expression of some semantic reality. Hence the artistic image is the main and most general form of expression in art, or the main way of artistic thinking, the existence of a work of art. Mimesis at

art is most fully realized through artistic images.

An artistic image

An image in general is a kind of subjective spiritual and psychic reality that arises in the inner world of a person in the act of perceiving any reality, in the process of contact with the outside world - in the first place, although, naturally, there are images of fantasy, imagination , dreams, hallucinations, etc., reflecting some subjective (internal) reality. On the broadest general philosophical plane, an image is a subjective copy of objective reality. An artistic image is an image of art, i.e. specially created in

An artistic image is an image of art, i.e. specially created in

the process of special creative activity according to specific (although, as a rule, unwritten) laws by the subject of art - the artist - is a phenomenon. In the future, we will only talk about the artistic image, therefore, for brevity, I call it simply an image.

In the history of aesthetics, Hegel was the first to pose the problem of the image in its modern form in the analysis of poetic art and outlined the main direction of its understanding and study. In the image and figurativeness, Hegel saw the specifics of art in general, and poetic art in particular. “In general,” he writes, “we can designate a poetic representation as a figurative representation, since it presents to our gaze not an abstract essence, but its concrete reality, not an accidental existence, but such a phenomenon in which directly through the external itself and its individual nine0003

267

we cognize the substantial in inseparable unity with it, and thus we find ourselves in the inner world of representation as one and the same integrity, both the concept of an object and its external being. In this respect there is a great difference between what gives us a figurative representation and what becomes clear to us through other modes of expression.

In this respect there is a great difference between what gives us a figurative representation and what becomes clear to us through other modes of expression.

The specificity and advantage of the image, according to Hegel, lies in the fact that, in contrast to the abstract verbal designation of an object or event that appeals to the rational consciousness, it represents an object to our inner vision in the fullness of its real appearance and essential substantiality. Hegel explains this with a simple example. When we say or read the words "sun" and "morning", it is clear to us what is being said, but neither the sun nor the morning appear before our eyes in their real form. And if, in fact, the poet (Homer) expresses the same thing with the words: “A young woman arose from darkness, with purple fingers Eos,” then we are given something more than a simple understanding of the sunrise. The place of abstract understanding is replaced by “real certainty”, and our inner gaze sees a holistic picture of the dawn in the unity of its rational (conceptual) content and concrete visual appearance. Therefore, in the image of Hegel, the poet's interest in the external side of the object from the point of view of the illumination of its "essence" in it is essential. In this regard, he distinguishes between images "in the proper sense" and images "in the improper" sense. The German philosopher refers to the first more or less direct, immediate, we would now say isomorphic, image (literal description) of the appearance of an object, and to the second - a mediated, figurative image of one object through another. Metaphors, comparisons, all kinds of figures of speech fall into this category of images. Hegel pays special attention to fantasy in creating poetic images. These ideas of the author of the monumental "Aesthetics" formed the foundation of the aesthetic understanding of the image in art, undergoing certain transformations, additions, changes, and sometimes complete denial at various stages in the development of aesthetic thought. nine0003

Therefore, in the image of Hegel, the poet's interest in the external side of the object from the point of view of the illumination of its "essence" in it is essential. In this regard, he distinguishes between images "in the proper sense" and images "in the improper" sense. The German philosopher refers to the first more or less direct, immediate, we would now say isomorphic, image (literal description) of the appearance of an object, and to the second - a mediated, figurative image of one object through another. Metaphors, comparisons, all kinds of figures of speech fall into this category of images. Hegel pays special attention to fantasy in creating poetic images. These ideas of the author of the monumental "Aesthetics" formed the foundation of the aesthetic understanding of the image in art, undergoing certain transformations, additions, changes, and sometimes complete denial at various stages in the development of aesthetic thought. nine0003

As a result of a relatively long historical development, today in classical aesthetics a fairly complete and multi-level idea of the image and figurative nature of art has developed. On the whole, an artistic image is understood as an organic spiritual-eidetic integrity, expressing Hegel. Aesthetics. T. 3. S. 384-385.

On the whole, an artistic image is understood as an organic spiritual-eidetic integrity, expressing Hegel. Aesthetics. T. 3. S. 384-385.

268

some reality in the mode of greater or lesser isomorphism (likeness of form) and realized (having existence) in its entirety only in the process of perception of a particular work of art by a particular recipient. It is then that the unique artistic world is fully revealed and actually functions, folded by the artist in the act of creating a work of art into its subject (painting,

musical, poetic, etc.) reality and unfolding already in some other concreteness (another hypostasis) in the inner world of the subject of perception. The image in its entirety is a complex process of artistic exploration of the world. It presupposes the presence of an objective or subjective reality, which gave impetus to the process of artistic display. It is more or less essentially subjectively transformed in the act of creating a work of art into a certain reality of the work itself. Then, in the act of perceiving this work, another process of transformation of features, form, even the essence of the original reality (the prototype, as they sometimes say in aesthetics) and the reality of the work of art (the "secondary" image) takes place. A final (already third) image appears, often very far from the first two, but nevertheless retaining something (this is the essence of isomorphism and the very principle of display) inherent in them and uniting them in a single system of figurative expression, or artistic display. nine0003

Then, in the act of perceiving this work, another process of transformation of features, form, even the essence of the original reality (the prototype, as they sometimes say in aesthetics) and the reality of the work of art (the "secondary" image) takes place. A final (already third) image appears, often very far from the first two, but nevertheless retaining something (this is the essence of isomorphism and the very principle of display) inherent in them and uniting them in a single system of figurative expression, or artistic display. nine0003

From this it is obvious that, along with the final, most general and complete image that arises during perception, aesthetics distinguishes a number of more particular understandings of the image, which it makes sense to dwell on at least briefly here. A work of art begins with the artist, more precisely, with a certain idea that arises in him before starting work on the work and is realized and concretized in the process of creativity as he works on the work. This initial, as a rule, still quite vague, idea is often already called an image, which is not entirely accurate, but can be understood as a kind of spiritual and emotional sketch of the future image. In the process of creating a work, in which, on the one hand, all the spiritual and spiritual forces of the artist participate, and on the other hand, the technical system of his skills in handling (processing) with a specific material from which, on the basis of which the work is created (stone, clay, paints , pencil and paper, sounds, words, theater actors, etc., in short - the entire arsenal of visual and expressive means of a given type or genre of art), the original image (= idea), as a rule, changes significantly. Often nothing remains of the original figurative and semantic sketch. He only does

This initial, as a rule, still quite vague, idea is often already called an image, which is not entirely accurate, but can be understood as a kind of spiritual and emotional sketch of the future image. In the process of creating a work, in which, on the one hand, all the spiritual and spiritual forces of the artist participate, and on the other hand, the technical system of his skills in handling (processing) with a specific material from which, on the basis of which the work is created (stone, clay, paints , pencil and paper, sounds, words, theater actors, etc., in short - the entire arsenal of visual and expressive means of a given type or genre of art), the original image (= idea), as a rule, changes significantly. Often nothing remains of the original figurative and semantic sketch. He only does

269

the role of the first stimulus for a rather spontaneous creative process. A work of art that has arisen is also, and already with great reason, called an image, which, in turn, has a number of figurative levels, or sub-images - images of a more local nature. The work as a whole is a concrete-sensual image of the spiritual objective-subjective unique world embodied in the material of this type of art, in which the artist lived in the process of creating this work. This image is a set of figurative and expressive units of this type of art, which is a structural, compositional, semantic integrity. This is an objectively existing work of art (a painting, an architectural structure, a novel, a poem, a symphony, a movie, etc.). nine0003

The work as a whole is a concrete-sensual image of the spiritual objective-subjective unique world embodied in the material of this type of art, in which the artist lived in the process of creating this work. This image is a set of figurative and expressive units of this type of art, which is a structural, compositional, semantic integrity. This is an objectively existing work of art (a painting, an architectural structure, a novel, a poem, a symphony, a movie, etc.). nine0003

Inside this folded image-work, we also find a number of smaller images determined by the figurative-expressive structure of this type of art. For the classification of images of this level, in particular, the degree of isomorphism (the external similarity of the image to the depicted object or phenomenon) is essential. The higher the level of isomorphism, the closer the image of the figurative-expressive level to the external form of the depicted fragment of reality, the more “literary” it is, i.e. lends itself to verbal description and evokes the corresponding "picture" representations in the recipient. For example, a picture of the historical genre, a classical landscape, a realistic story, etc. At the same time, it is not so important whether we are talking about the visual arts proper (painting, theater, cinema) or about music and literature. With a high degree of isomorphism, "picture" images or representations arise on any basis. And they do not always contribute to the organic development of the actual artistic image of the whole work. Quite often, it is this level of figurativeness that turns out to be oriented towards non-aesthetic goals (social, political, etc.). nine0003

For example, a picture of the historical genre, a classical landscape, a realistic story, etc. At the same time, it is not so important whether we are talking about the visual arts proper (painting, theater, cinema) or about music and literature. With a high degree of isomorphism, "picture" images or representations arise on any basis. And they do not always contribute to the organic development of the actual artistic image of the whole work. Quite often, it is this level of figurativeness that turns out to be oriented towards non-aesthetic goals (social, political, etc.). nine0003

However, ideally, all these images are included in the structure of the general artistic image. For example, for literature they talk about the plot as an image of a certain life (real, probabilistic, fantastic, etc.) situation, about the images of specific heroes of this work (images of Pechorin, Faust, Raskolnikov, etc.), about the image of nature in specific descriptions, etc. The same applies to painting, theater, cinema. More abstract (with a lesser degree of isomorphism) and less amenable to concrete verbalization are images in

More abstract (with a lesser degree of isomorphism) and less amenable to concrete verbalization are images in

works of architecture, music or abstract art, but even there one can speak of

270

expressive figurative structures. For example, in connection with some completely abstract “Composition” by V. Kandinsky, where visual-subject isomorphism is completely absent, we can talk about a compositional image based on the structural organization of color forms, color relationships, balance or dissonance of color masses, etc. .

Finally, in the act of perception (which, by the way, begins to be realized already in the process of creativity, when the artist acts as the first and extremely active recipient of his emerging work, correcting the image as it develops), a work of art is realized, as already mentioned, the main image of this work for which it was actually brought into being. In the spiritual and spiritual world of the subject of perception, a certain ideal reality arises, in which everything is connected, fused into an organic integrity, there is nothing superfluous and no flaw or lack is felt. It simultaneously belongs to the given subject (and only to him, because another subject will already have a different reality, a different image on the basis of the same work of art), a work of art (it arises only on the basis of this particular work) and the Universe as a whole, because it really introduces the recipient into the process of perception (i.e., the existence of a given reality, a given image) to the universal pleroma of being. Traditional aesthetics describes this supreme event of art in different ways, but the meaning remains the same: comprehension of the truth of being, the essence of a given work, the essence of the depicted phenomenon or object; the manifestation of truth, the formation of truth, the comprehension of an idea, an eidos; contemplation of the beauty of being, familiarization with ideal beauty; catharsis, ecstasy, insight, etc. etc. The final stage of perception of a work of art is experienced and realized as a kind of breakthrough of the subject of perception to some levels of reality unknown to him, accompanied by a feeling of fullness of being, unusual lightness, exaltation, spiritual joy.

It simultaneously belongs to the given subject (and only to him, because another subject will already have a different reality, a different image on the basis of the same work of art), a work of art (it arises only on the basis of this particular work) and the Universe as a whole, because it really introduces the recipient into the process of perception (i.e., the existence of a given reality, a given image) to the universal pleroma of being. Traditional aesthetics describes this supreme event of art in different ways, but the meaning remains the same: comprehension of the truth of being, the essence of a given work, the essence of the depicted phenomenon or object; the manifestation of truth, the formation of truth, the comprehension of an idea, an eidos; contemplation of the beauty of being, familiarization with ideal beauty; catharsis, ecstasy, insight, etc. etc. The final stage of perception of a work of art is experienced and realized as a kind of breakthrough of the subject of perception to some levels of reality unknown to him, accompanied by a feeling of fullness of being, unusual lightness, exaltation, spiritual joy. nine0003

nine0003

At the same time, it does not matter at all what the specific, intellectually perceived content of the work (its superficial literary-utilitarian level), or more or less specific visual, auditory images of the psyche (emotional-psychic level), arising on its basis. For the complete and essential realization of the artistic image, it is important and significant that the work be organized according to artistic and aesthetic laws, i.e. must ultimately cause aesthetic pleasure in the recipient, which is an indicator of the reality of the contact - the entry of the subject of perception from

271

with the help of the updated image to the level of the true being of the Universe.

Take, for example, the famous painting "Sunflowers" by Van Gogh (1888, Munich, Neue Pinakothek), depicting a bouquet of sunflowers in a jug. On the “literary”-subject pictorial level, we see on the canvas only a bouquet of sunflowers in a ceramic jug standing on a table against a greenish wall. There is a visual image of a jar, and an image of a bouquet of sunflowers, and very different images of each of the 12 flowers, which can all be described in sufficient detail in words (their position, shape, colors, degree of maturity, some even have the number of petals). However, these descriptions will still have only an indirect relation to the integral artistic image of each depicted object (one can also talk about this), and even more so to the artistic image of the entire work. The latter is formed in the psyche of the viewer on the basis of such a multitude of visual elements of the picture that make up an organic (one might say, harmonic) integrity, and a mass of all kinds of subjective impulses (associative, memory, artistic experience of the viewer, his knowledge, his mood at the time of perception, etc. . ) that all this defies any intellectual accounting or description. However, if we really have a real work of art before us, like these “Sunflowers”, then all this mass of objective (coming from the picture) and subjective impulses that arose in connection with them and on their basis forms such an integral reality in the soul of each viewer, such a visual and spiritual an image that arouses in us a powerful explosion of feelings, delivers indescribable joy, elevates us to the level of such a really felt and experienced fullness of being that we never achieve in ordinary (outside of aesthetic experience) life.

There is a visual image of a jar, and an image of a bouquet of sunflowers, and very different images of each of the 12 flowers, which can all be described in sufficient detail in words (their position, shape, colors, degree of maturity, some even have the number of petals). However, these descriptions will still have only an indirect relation to the integral artistic image of each depicted object (one can also talk about this), and even more so to the artistic image of the entire work. The latter is formed in the psyche of the viewer on the basis of such a multitude of visual elements of the picture that make up an organic (one might say, harmonic) integrity, and a mass of all kinds of subjective impulses (associative, memory, artistic experience of the viewer, his knowledge, his mood at the time of perception, etc. . ) that all this defies any intellectual accounting or description. However, if we really have a real work of art before us, like these “Sunflowers”, then all this mass of objective (coming from the picture) and subjective impulses that arose in connection with them and on their basis forms such an integral reality in the soul of each viewer, such a visual and spiritual an image that arouses in us a powerful explosion of feelings, delivers indescribable joy, elevates us to the level of such a really felt and experienced fullness of being that we never achieve in ordinary (outside of aesthetic experience) life. nine0003

nine0003

Such is the reality, the fact of the true existence of the artistic image as the essential basis of art. Any art, if it organizes its works according to unwritten, infinitely diverse, but really existing artistic laws.

5 principles of the Stanislavsky system

5 principles of the Stanislavsky systemjournal

5 principles of the Stanislavsky system

The Stanislavsky system is a theory of stage performance developed by the Russian director and teacher Konstantin Sergeevich Stanislavsky at the beginning of the 20th century. The five main principles of his system still remain relevant and underlie the methods of training actors in theater universities around the world. nine0003

The truth of experiences

The truth of life on stage is one of the main principles of Stanislavsky's system. It argues that there is a direct connection between the emotions of the actor and the feelings of the viewer: the more the actor feels his game and more accurately conveys the feelings of the hero, the more the viewer believes what is happening on stage. If the actor has not mastered the skill of believable acting, his work is judged by the famous "I don't believe it!" Acting, serving on the stage, lack of life and feelings - every actor is afraid of these characteristics, because they kill the connection with the audience and the success of the whole game. nine0003

If the actor has not mastered the skill of believable acting, his work is judged by the famous "I don't believe it!" Acting, serving on the stage, lack of life and feelings - every actor is afraid of these characteristics, because they kill the connection with the audience and the success of the whole game. nine0003

From the point of view of acting, according to Stanislavsky, truth

experiences are divided into two types:

1. True truth is those experiences that a person really experiences at different moments of his life. There is no need for a game here, emotions appear unconsciously, by themselves, others perceive such experiences correctly, trust them.

2. Stage truth - it is called artistic truth, because it first appears in artistic (drawn, imaginary) life, and only then is it transferred by the actor to the stage. Creating such a truth requires careful preparation, the actor must learn not only to believe in what is happening, but also to live in every moment. nine0003

nine0003

The great teacher demanded from his students not only to act truthfully – he taught how to get used to the image of the character, transform themselves internally and look at the game through the eyes of his hero. Many researchers of stage art emphasize that before Stanislavsky, people simply played in the theater, his system taught the actors how to live. The life of an actor on the stage is the absence of the slightest hint of falsehood and pretense, feigned feelings. During the performance, the viewer must forget that he is in the theater, believe and empathize with everything that he sees on the stage. nine0003

Dealing with circumstances

An actor cannot learn to play his role truthfully without being able to understand the circumstances in which the stage character exists. Thoughts, emotions and behavior depend on the circumstances, the actor must understand the logic of his hero, act in the same way as he would have done in a given situation.

Acting on the stage will be believable if the actor knows not the type of emotional manifestations inherent in the character, but the reasons that caused these emotions. It is necessary to understand the conditions in which the hero is and lives, the obligatory acting skill is the ability to invent and develop these circumstances. The actor must pass the situation through himself, say to himself: “This happened to me, I am this person.” nine0003

The artist must pay attention to three circles of circumstance:

1. The big circle is the general social, political and historical setting in which the character finds himself.

2. Middle circle - this includes the details of the hero's life: his financial and marital status, features of life, age and other details.

3. Small circle - those events that are happening to the character at the moment and affect his feelings, desires, goals and behavior. The task of the actor is to make the viewer see the existing circumstances and understand that they form the character and actions of the character. nine0003

nine0003

Is acting a good fit for you?

Take our creativity test and find out.

| Take the test |

Playing the Here and Now

An important skill for an actor is to play the here and now. This means that each time he must experience in a new way the role that he performs not for the first time, any action must be born anew on the stage. The difficulty of following this principle is that the actor plays the same role many times in a row, the character's behavior becomes a habit, turns into a cliché. nine0003

The artist, who has learned to live in his role again each time, prolongs the life of the performance, does not allow it to grow old and annoy the viewer. Therefore, exercises for actors according to the Stanislavsky system necessarily include tasks that help to evoke feelings in real time - here and now. The purpose of such tasks is to teach the actor to focus on their emotions, think about what is happening on stage, feel contact with partners and control the attention of the audience.

Actor cultivation

In order to achieve success, an actor must constantly improve himself, cultivate the qualities necessary for work. These include:

- observation - the ability to notice in everyday life and transfer interesting situations to the stage, the nature of memorable personalities;

- memory (verbal, figurative, emotional) - the actor must memorize well not only the text of the role, but be able to easily recall the feelings experienced once, to feel them again;

- attention is a multifaceted quality: an actor needs to correctly distribute his attention between stage partners and the audience;

- the ability to concentrate on the task - in any situation, the actor must be able to control his emotions, apply the principle of the game "here and now";

- the ability to be distracted from minor details - an artist on stage can often be distracted from the role by technical overlays, a true professional should not pay attention to them;

- imagination - without the development of acting fantasy, the game becomes shackled, and the image of the character turns out to be incomplete and implausible.

nine0170

nine0170

An important direction in the self-improvement of an actor is work on the body. Stanislavsky emphasized that the physical apparatus of a person must be kept in order, developed and used in full. This includes the health and beauty of the body, fitness of muscles, plasticity and harmony of movements, proper breathing. An actor who knows about the perfect work of his body feels confident on stage. If the artist has all the listed acting qualities, his creative potential is revealed, giving him unlimited freedom. nine0003

Interaction with stage partners

Theater is a collective work, so the actor must learn to work with partners. Between colleagues there should be an atmosphere of trust, full understanding and mutual assistance. Partners who feel each other achieve the perfect game and win the hearts of the audience. Konstantin Sergeevich attached particular importance to the live interaction of partners on stage. His approach to this issue changed and improved, the director argued that the contact should be direct, "from soul to soul." He also did not deny the importance of communication through movements, facial expressions and physical sense organs, he reflected on the connection between the soul and the body, physical and mental state (the book "The work of an actor on himself", the chapter "Communication"). Stanislavsky emphasized that the interaction of an actor with partners is the most subtle process of stage struggle, which can take various forms. When communicating, a person encounters the active will of a partner, adapts to it, opposes it, changes his behavior. The actor must have a high artistic technique in order not to lose touch with his partner, to preserve the realistic life of the characters on stage. The ideal of partner cooperation is the organic nature of creativity, when throughout the performance an internal connection is established between the actors, a special sensitivity to each other develops.

His approach to this issue changed and improved, the director argued that the contact should be direct, "from soul to soul." He also did not deny the importance of communication through movements, facial expressions and physical sense organs, he reflected on the connection between the soul and the body, physical and mental state (the book "The work of an actor on himself", the chapter "Communication"). Stanislavsky emphasized that the interaction of an actor with partners is the most subtle process of stage struggle, which can take various forms. When communicating, a person encounters the active will of a partner, adapts to it, opposes it, changes his behavior. The actor must have a high artistic technique in order not to lose touch with his partner, to preserve the realistic life of the characters on stage. The ideal of partner cooperation is the organic nature of creativity, when throughout the performance an internal connection is established between the actors, a special sensitivity to each other develops.